Volume Four: Commonplace Edition, #1

This time it's a bit different

“What if we could take a taste of the maybe

Beyond what's been known and been named?”

~ Envy Green, The Arcadian Wild

Introduction

What are dreams made of? Snippets of conversations, passing thoughts, Ineffable ideas just beyond reach, what we see, watch, and read. And the best ideas often spring up from the most transient, passing things. You and I are built on ideas, the highest of which was, “let us create man in our image,” the smaller of which are thinkers in our time; Dickens, Calvin, Rousseau, Plato, and others. For better or for worse, the ideas of these figures have shaped us, changed us, even enlightened us.

Today you’re being introduced to the first Commonplace Edition - a collection of ideas and thoughts from the past. It’s as if I went back in time and asked great writers to give me a piece for this literary journal. These will come out every once in a while, in between the regular volumes.

Why a Commonplace Edition? For multiple reasons. Because the past informs the present and gives a striking amount of perspective to the future. Because many of the writers for this journal were and are inspired by the Greats of the past. And, quite frankly, because putting together a bunch of different writers from different ages - some of which butt heads and go to war - is only too fun. It’s only right every once in a while, to give those old works a nod. My hope is that the snippets of the works I add here will inspire you to read them in full, wrestle with them, and perhaps see things in a new light…

“In your schooldays most of you who read this book made acquaintance with the noble building of Euclid’s geometry, and you remember — perhaps with more respect than love — the magnificent structure, on the lofty staircase of which you were chased about for uncounted hours by conscientious teachers. By reason of your past experience, you would certainly regard everyone with disdain who should pronounce even the most out-of-the-way proposition of this science to be untrue. But perhaps this feeling of proud certainty would leave you immediately if someone were to ask you: “What, then, do you mean by the assertion that these propositions are true?” Let us proceed to give this question a little consideration.”

~ the very beginning of General Relativity, in which Einstein asks us to think, “what if this isn’t true, what I believed all along?” He referred to Euclid, but I could ask you the same question, and so could the Greats of the past. They may be wrong, of course, but it’s worth looking.

Thank you to Abby Skolny for her wonderful artwork! Here’s an early sketch - the complete image is at the bottom of this volume.

“I've always loved dragons, but the unfortunate thing is that they're very not easy to draw. At least for me. But occasionally, you have a vision for a drawing and you're able to make it work, even if not quite as high quality as your expectations, and that's what this drawing was for me. I wanted to try a more dynamic perspective than I usually do, and it worked out well for this.” ~ Abby Skolny

Contents

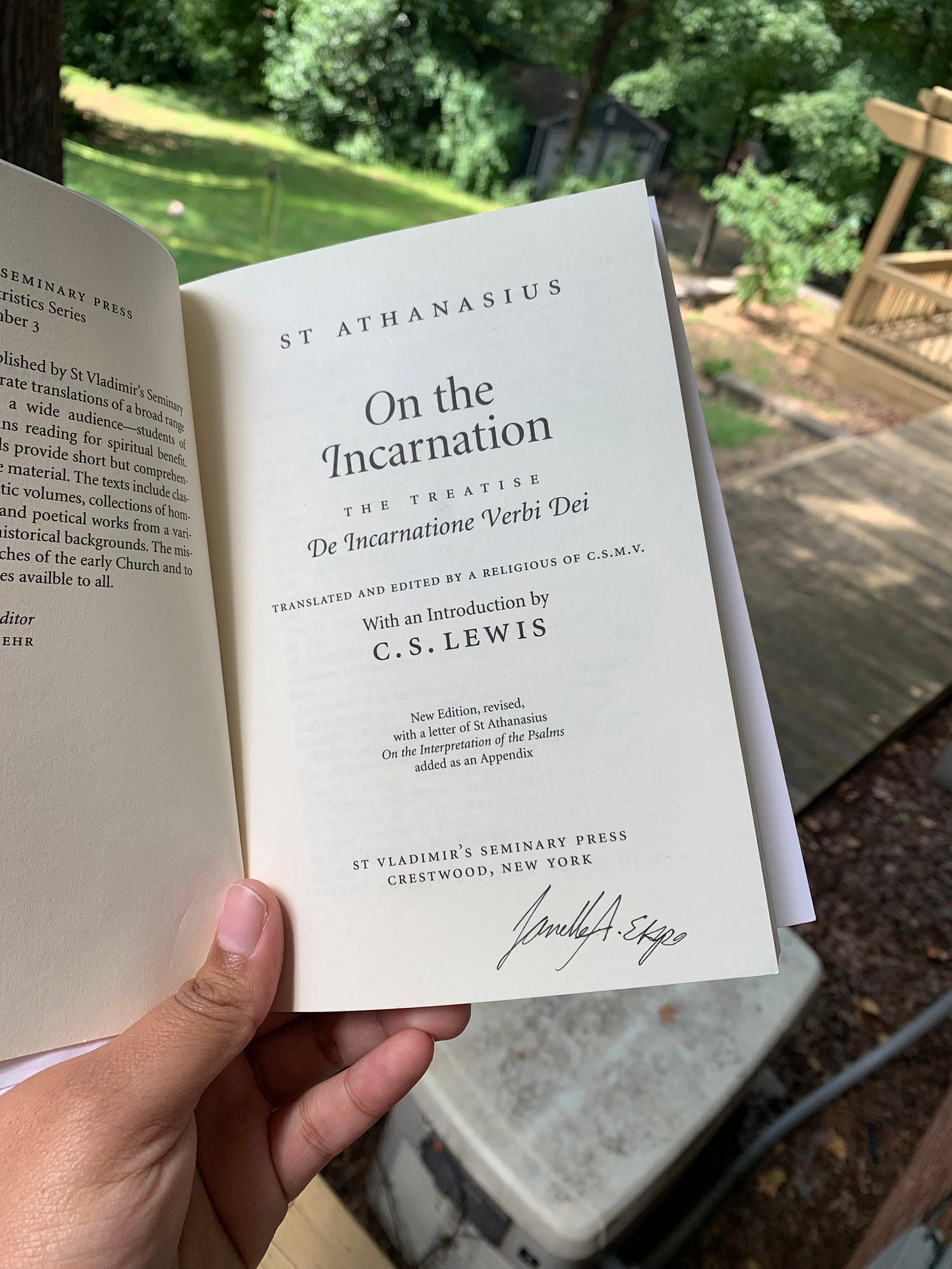

Excerpts from C. S. Lewis’ introduction to Athanasius on the Incarnation

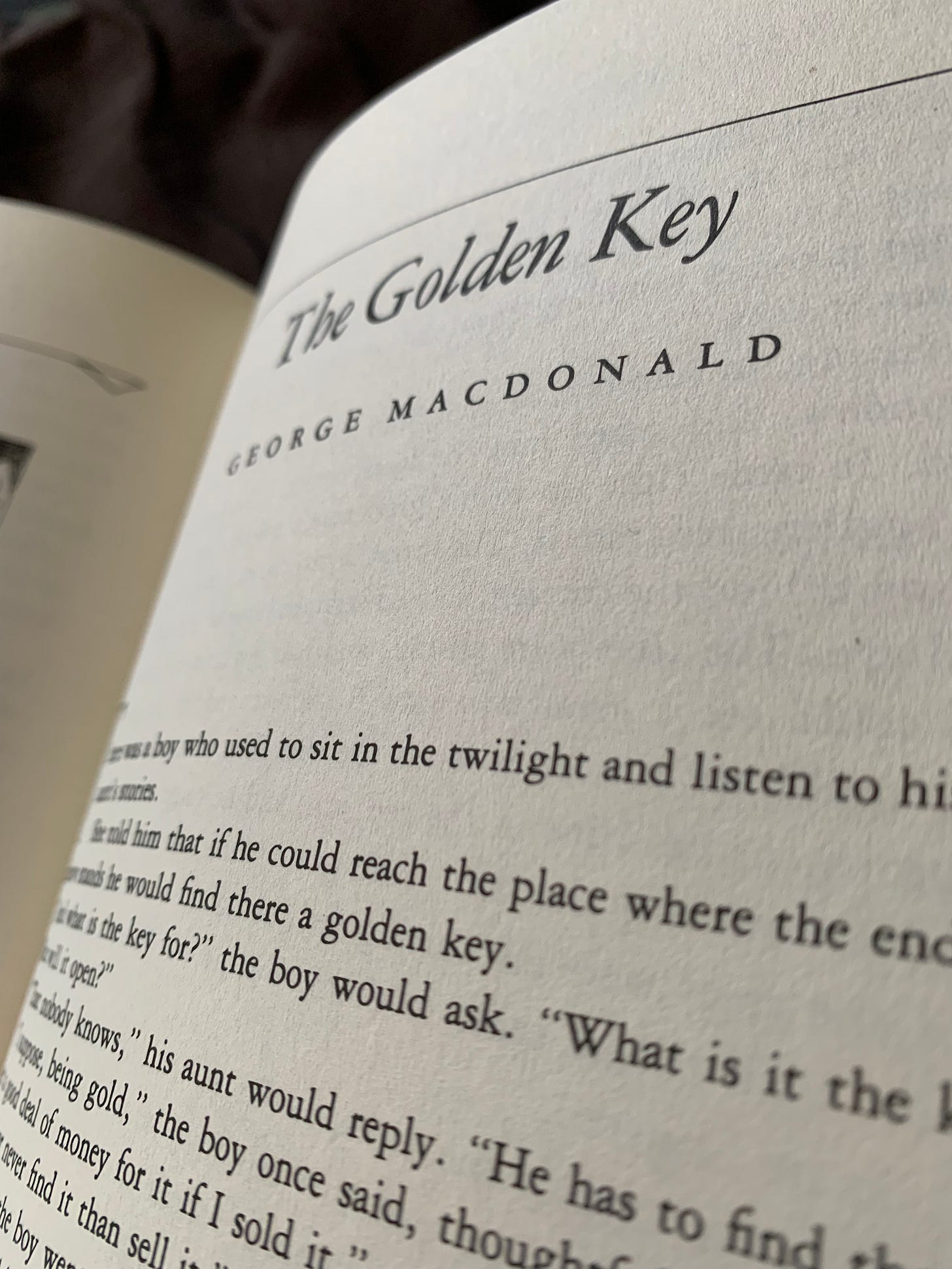

Excerpts from The Golden Key, by George MacDonald

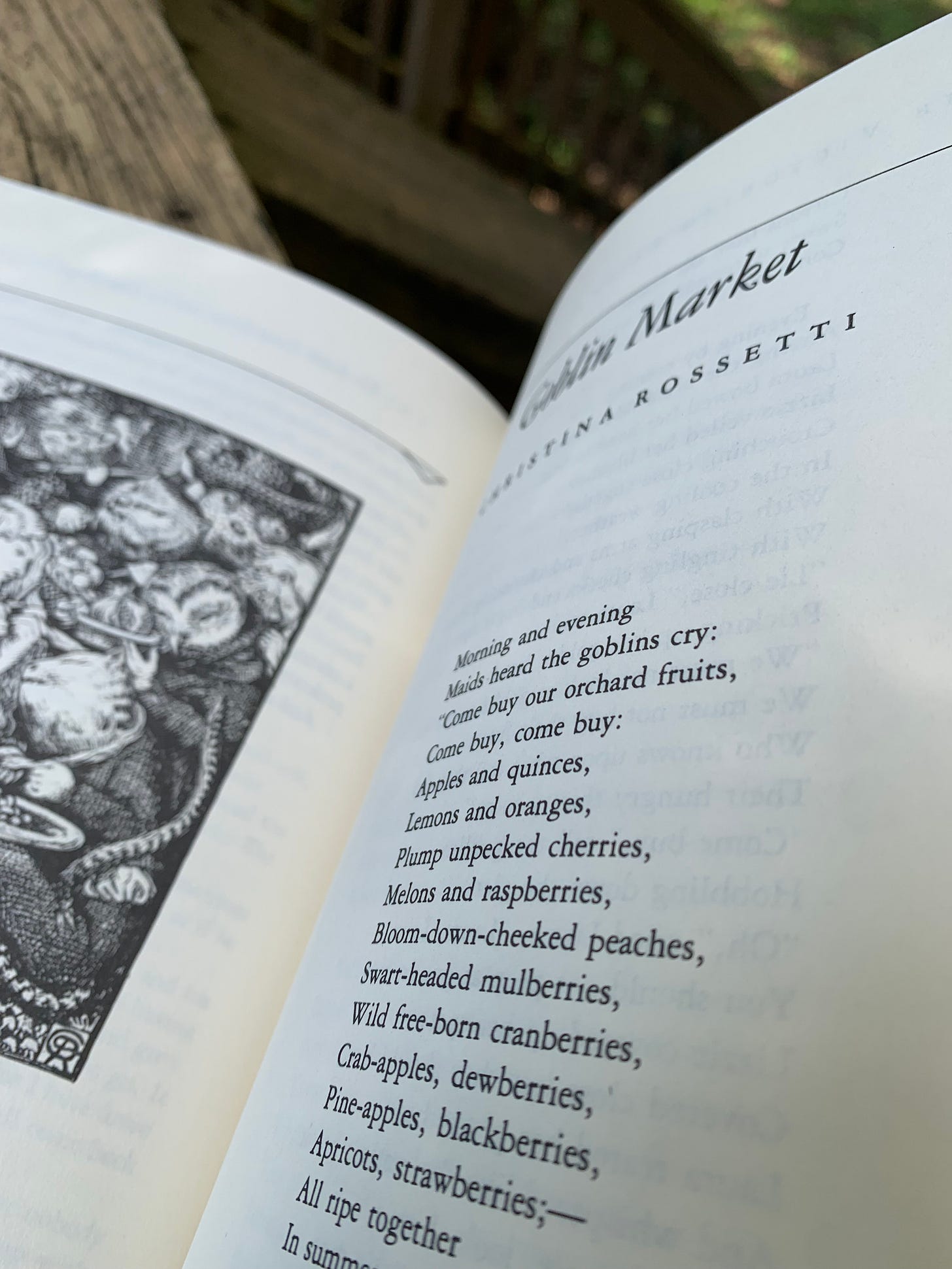

Poem pieces from Rossetti, William Blake, and Gluck

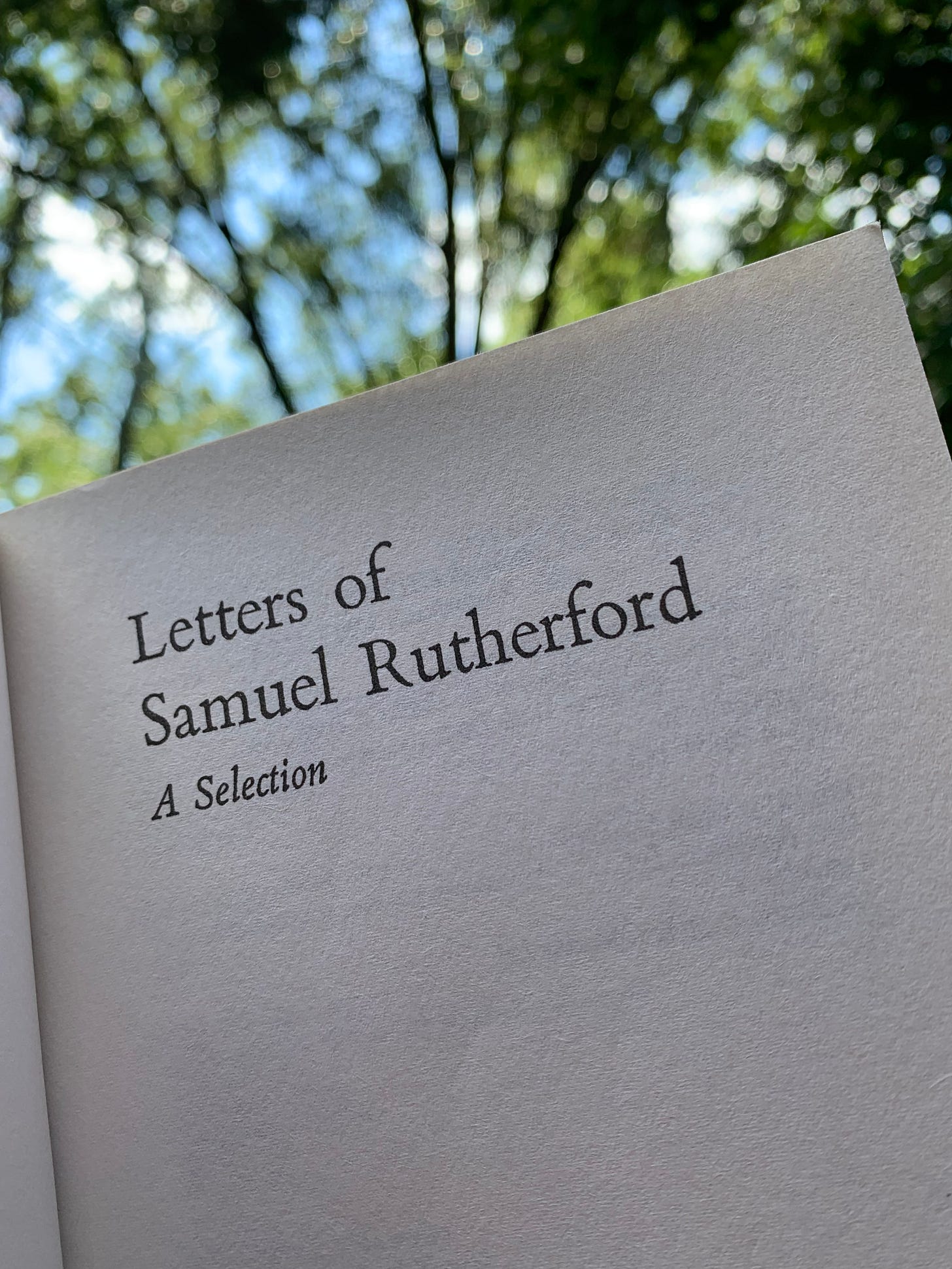

A letter of Samual Rutherford

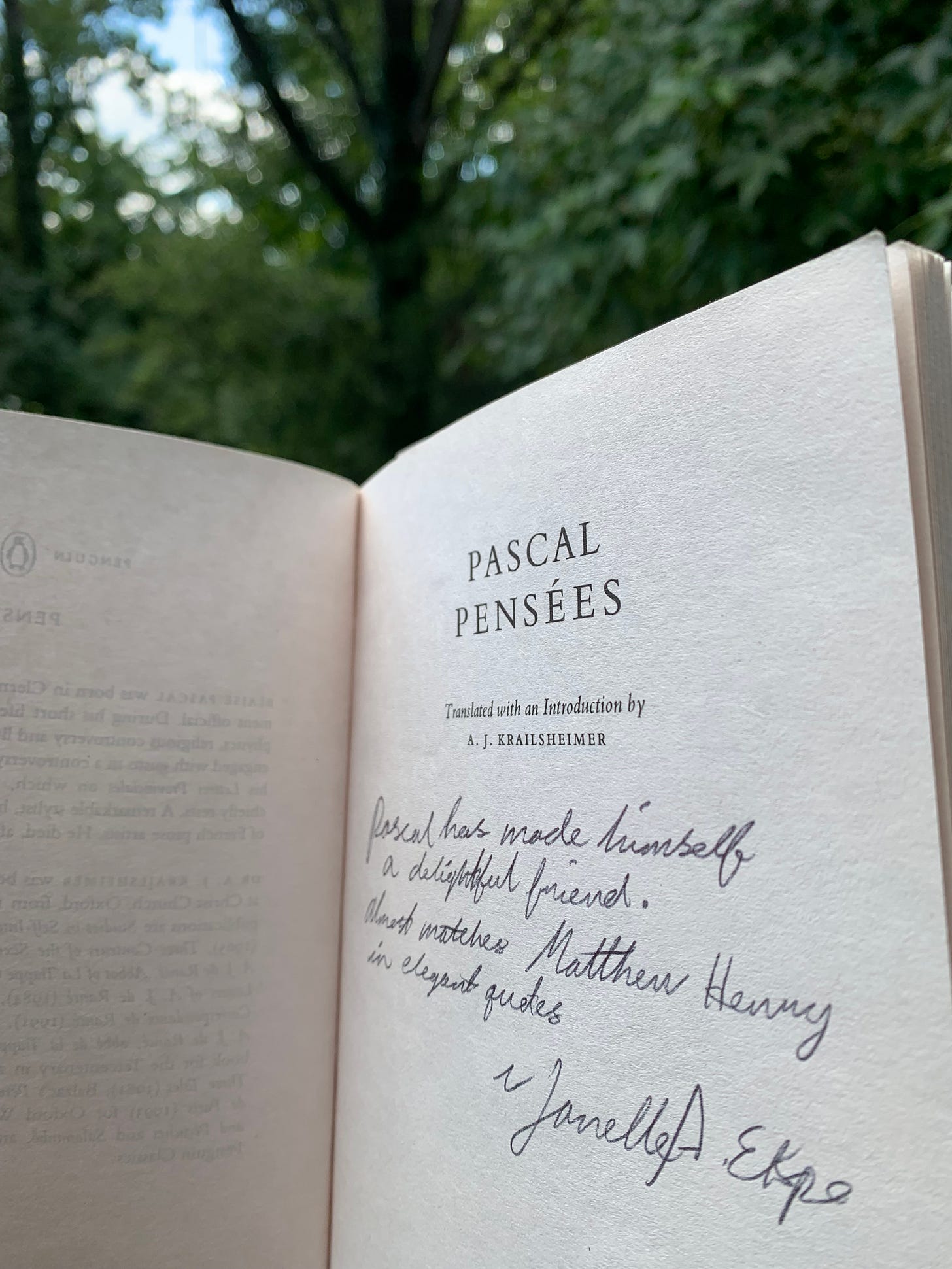

Some Pensées of Pascal

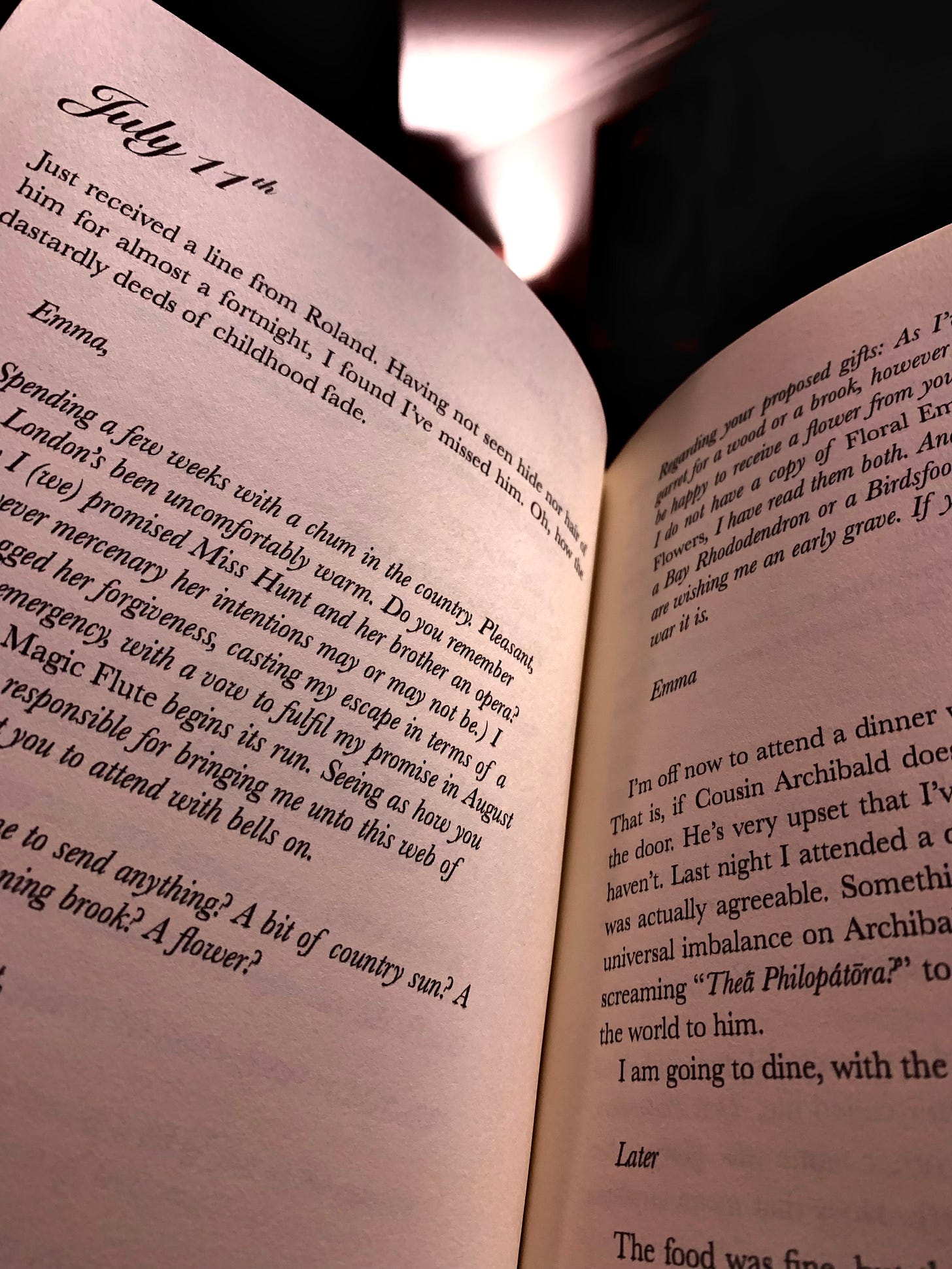

A little Emma M. Lion, by Beth Brower (not an old book. Don’t tell anyone.)

There is a strange idea abroad that in every subject the ancient books should be read only by the professionals, and that the amateur should content himself with the modern books. Thus I have found as a tutor in English Literature that if the average student wants to find out something about Platonism, the very last thing he thinks of doing is to take a translation of Plato off the library shelf and read the Symposium. He would rather read some dreary modern book ten times as long, all about “isms” and influences and only once in twelve pages telling him what Plato actually said. The error is rather an amiable one, for it springs from humility. The student is half afraid to meet one of the great philosophers face to face. He feels himself inadequate and thinks he will not understand him. But if he only knew, the great man, just because of his greatness, is much more intelligible than his modern commentator. The simplest student will be able to understand, if not all, yet a very great deal of what Plato said; but hardly anyone can understand some modern books on Platonism. It has always therefore been one of my main endeavours as a teacher to persuade the young that firsthand knowledge is not only more worth acquiring than secondhand knowledge, but is usually much easier and more delightful to acquire.

“The student is half afraid to meet one of the great philosophers face to face. He feels himself inadequate and thinks he will not understand him. But if he only knew, the great man, just because of his greatness, is much more intelligible than his modern commentator.”

… If you join at eleven o’clock a conversation which began at eight you will often not see the real bearing of what is said. Remarks which seem to you very ordinary will produce laughter or irritation and you will not see why – the reason, of course, being that the earlier stages of the conversation have given them a special point. In the same way sentences in a modern book which look quite ordinary may be directed at some other book; in this way you may be led to accept what you would have indignantly rejected if you knew its real significance. The only safety is to have a standard of plain, central Christianity (“mere Christianity” as Baxter called it) which puts the controversies of the moment in their proper perspective. Such a standard can be acquired only from the old books. It is a good rule, after reading a new book, never to allow yourself another new one till you have read an old one in between. If that is too much for you, you should at least read one old one to every three new ones.

“It is a good rule, after reading a new book, never to allow yourself another new one till you have read an old one in between.”

Every age has its own outlook. It is specially good at seeing certain truths and specially liable to make certain mistakes. We all, therefore, need the books that will correct the characteristic mistakes of our own period. And that means the old books. All contemporary writers share to some extent the contemporary outlook – even those, like myself, who seem most opposed to it. Nothing strikes me more when I read the controversies of past ages than the fact that both sides were usually assuming without question a good deal which we should now absolutely deny. They thought that they were as completely opposed as two sides could be, but in fact they were all the time secretly united – united with each other and against earlier and later ages – by a great mass of common assumptions… The only palliative [against the danger of the assumptions of our age] is to keep the clean sea breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds, and this can be done only by reading old books. Not, of course, that there is any magic about the past. People were no cleverer then than they are now; they made as many mistakes as we. But not the same mistakes. They will not flatter us in the errors we are already committing; and their own errors, being now open and palpable, will not endanger us. Two heads are better than one, not because either is infallible, but because they are unlikely to go wrong in the same direction. To be sure, the books of the future would be just as good a corrective as the books of the past, but unfortunately we cannot get at them.

“…keep the clean sea breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds, and this can be done only by reading old books.”

The Greek philosophers have compiled many works with persuasiveness and much skill in words; but what fruit have they to show for this such has the cross of Christ? ~ Athanasius, On the Incarnation

He took his key. It turned in the lock to the sounds of Aolian music. A door opened upon slow hinges, and disclosed a winding stair within. The key vanished from his fingers. Tangle went up. Mossy followed. The door closed behind them. They climbed out of the earth ; and, still climbing, rose above it. They were in the rainbow. Far abroad, over ocean and land, they could see through its transparent walls the earth beneath their feet. Stairs beside stairs wound up together, and beautiful beings of all ages climbed along with them.

They knew that they were going up to the country whence the shadows fall.

And by this time I think they must have got there.

~ The Golden Key, George MacDonald

“For there is no friend like a sister

In calm or stormy weather;

To cheer one on the tedious way,

To fetch one if one goes astray,

To lift one if one totters down,

To strengthen whilst one stands.”

~ The Goblin Market, Christina Rossetti

Hear the voice of the Bard,

Who present, past, and future, sees;

Whose ears have heard

The Holy Word

That walk'd among the ancient trees;

Calling the lapsed soul,

And weeping in the evening dew;

That might control

The starry pole,

And fallen, fallen light renew!

'O Earth, O Earth, return!

Arise from out the dewy grass!

Night is worn,

And the morn

Rises from the slumbrous mass.

'Turn away no more;

Why wilt thou turn away?

The starry floor,

The watery shore,

Is given thee till the break of day.'

~ Hear the Voice, William Blake

… I ask you, how much beauty

can a person bear? It is

heavier than ugliness, even the burden

of emptiness is nothing beside it.

~ Baskets, Louise Gluck

To Marion M’Naught

the prospect of exile to Aberdeen

Edinburgh, 5 April 1636

Honored and dearest Lord:

Grace, mercy and peace be to you. I am well and my soul prospereth. I find Christ with me. I burden no man, I want nothing, no face looketh on me but it laugheth on me. Sweet, sweet is the Lord’s cross. I overcome my heaviness. My Bridegroom's love-blinks fatten my weary soul. I soon go to my King’s palace in Aberdeen. Tongue and pen and wit cannot express my joy.

Remember my love to Jean Gordon, to my sister, Jean Brown, to Grizel, to your husband. Thus in haste. Grace be with you.

Yours in his only Lord Jesus,

S. R.

P. S. My charge is to you to believe, rejoice, sing and triumph. Christ has said to me, mercy, mercy, grace and peace for Marion M’Naught.

“My chains are gilded over with gold.”

Man is only a reed, the weakest in nature, but he is a thinking reed. There is no need for the whole universe to take up arms to crush him: a vapour, a drop of water is enough to kill him. But even if the universe were to crush him, man would still be nobler than his slayer, because he knows that he is dying and the advantage the universe has over him. The universe knows none of this.

Thus all our dignity consists in thought. It is on thought that we must depend for our recovery, not on space and time, which we could never fill. Let us then strive to think well: that is the basic principle of morality…

Be comforted; it is not from yourself that you must expect it, but on the contrary, you must expect it by expecting nothing from yourself…

We never keep to the present. We recall the past; we anticipate the future as if we found it too slow in coming and were trying to hurry it up, or we recall the past as if to stay its too rapid flight. We are so unwise that we wander about in times that do not belong to us, and do not think of the only one that does; so vain that we dream of times that are not and blindly flee the only one that is. The fact is that the present usually hurts. We thrust it out of sight because it distresses us, and if we find it enjoyable, we are sorry to see it slip away. We try to give it the support of the future, and think how we are going to arrange things over which we have no control for a time we can never be sure of reaching.

Let each of us examine his thoughts; he will find them wholly concerned with the past or the future. We almost never think of the present, and if we do think of it, it is only to see what light it throws on our plans for the future. The present is never our end. The past and the present are our means, the future alone our end. Thus we never actually live, but hope to live, and since we are always planning how to be happy, it is inevitable that we should never be so.

Pascal, Pensées, 200, 202, 47

… I am not the heroine of a novel. I am flesh, blood—interesting enough on occasion, with dull edges here and there, living a life of the expected and the unexpected, the wanted and the worst of the unwanted…

Two pages in and I’m having a high dispute with myself and Mr. Emerson. I’ve looked, and there are thirty-nine pages to go.

Argument indeed. Mr. Pierce knew what he was speaking of.

I’m not certain tonight if I am a reader of a pugilist? Perhaps they are one and the same.

~ The Unselected Journals of Emma M. Lion, Vol. 3, Beth Brower

“I am a great eater of beef, and, I believe, that does harm to my wit.” ~ Twelfth Night, Shakespeare

Concluding Thoughts

I hope you enjoyed the first Commonplace Edition of this journal. As always, if you have submissions (even a favorite quote for the next Commonplace Edition!) Be encouraged to send them in. Guidelines: ASSW Submission.

And again, thank you for reading.

Janelle Ekpo, Editor

“Tongue and pen and wit cannot express my joy.” ~ Samuel Rutherford

Oh, this is an absolutely beautiful collection, Janelle! I enjoyed it thoroughly--and now wish to find The Golden Key for further enjoyment. ❤📚